Words matter.

How discriminatory covenants were used to segregate Minnesota communities.

In post-Civil War Minnesota and across the country, developers, real estate agents, and local, state and federal governments prohibited Black Americans from realizing their full rights and opportunities as citizens. Governments and developers deliberately used discriminatory covenants to create segregated communities and build wealth for the white community at the expense of the Black community and other people of color.

These “white-only” covenants restricted families along racial and ethnic lines from owning homes in the majority of neighborhoods in our cities.

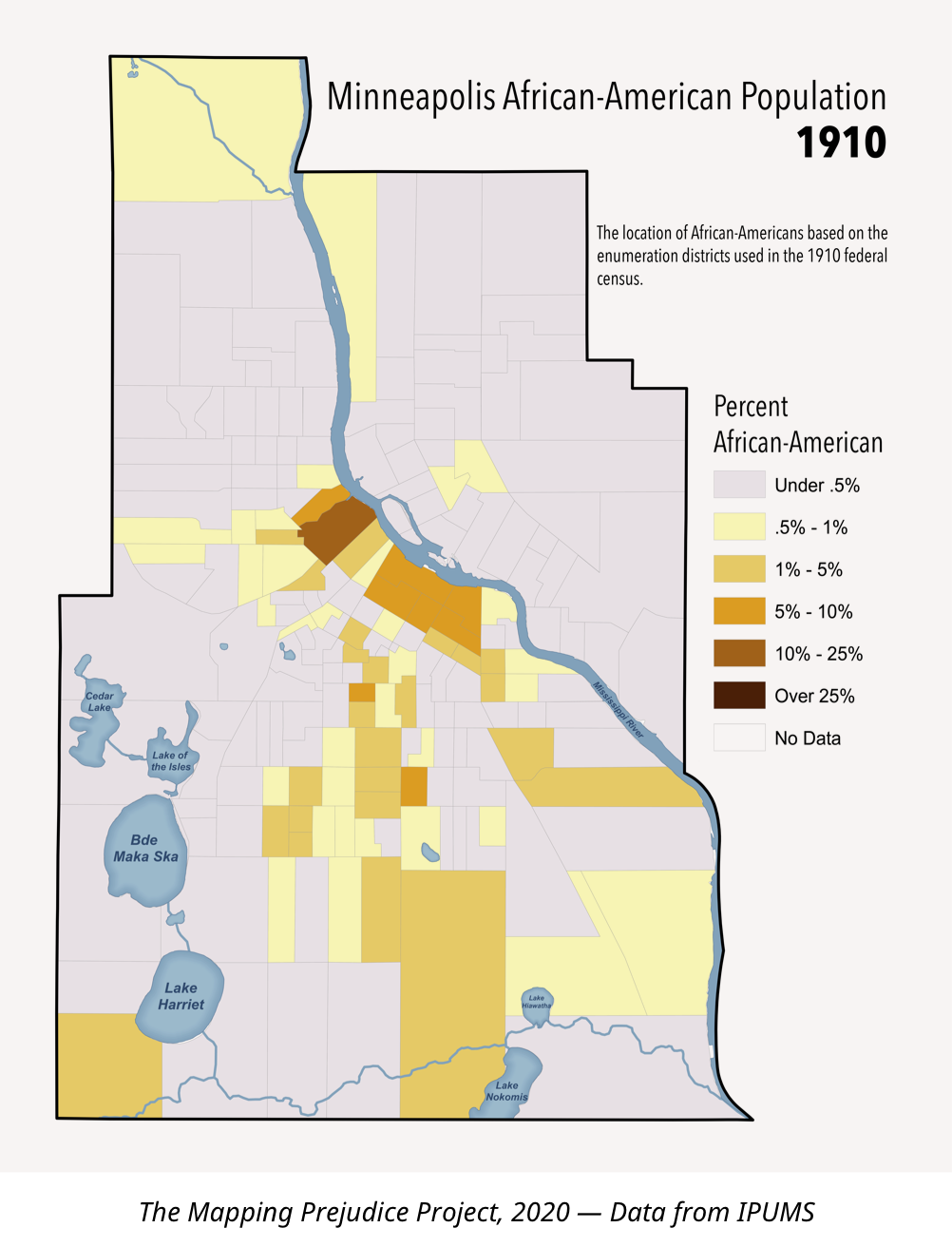

In Minneapolis, the first racially restrictive deed appeared in 1910, when Henry and Leonora Scott sold a property on 35th Avenue South to Nels Anderson. The deed contained what would become a common restriction:

…the premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.

…the premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.

Separate and unequal.

When the racially restrictive deed above was written, Minneapolis was not particularly segregated. But covenants changed the landscape of the city. As racially restrictive deeds spread, Black Americans were pushed into a few small areas of the city. And as the number of Black residents continued to climb, even larger swaths of the city became entirely white.

This laid the groundwork for our contemporary patterns of residential segregation. Many Twin Cities suburban developments (sometimes officially sanctioned by local governments) adopted the practice of segregating communities through the use of racially restrictive covenants in the first half of the 20th century.

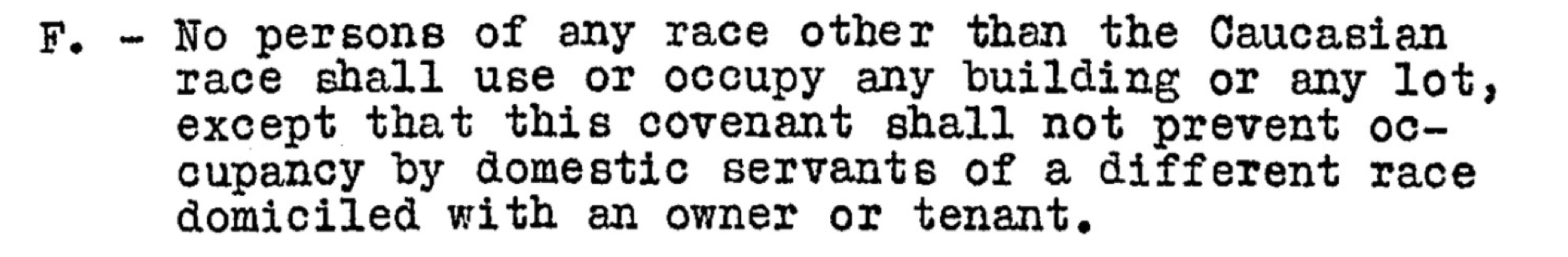

For example, the Betcher’s Addition Plat, approved by the City of Richfield in 1937, had the following language: “No race or nationality other than white persons shall use or occupy any dwelling on any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent the occupancy by domestic servants of a different race when employed by any owner or tenant.”

Another common Minneapolis covenant reads: “the said premises shall not at any time be sold, conveyed, leased, or sublet, or occupied by any person or persons who are not full bloods of the so-called Caucasian or White race.”

Built on a foundation of racism.

In the 1940s, the NAACP, recognizing covenants as a fundamental threat to racial equality, launched a sustained legal campaign against them. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that covenants were unenforceable in the landmark Shelley v. Kraemer case. By 1953, the Minnesota Legislature prohibited the use of racial restrictions in warranty deeds. But covenants remained commonplace in much of the nation until 1968, when the federal Fair Housing Act made them explicitly illegal.

Last place.

Minnesota is ranked 50th among all states for Black homeownership.

While 78% of white families own homes in the Twin Cities, only 25% of African American families own homes.

Despite these legal victories, restrictions were still being used across Minnesota to keep people of color out of safe and affordable housing. Discriminatory covenants dovetailed with redlining and predatory lending practices to continue the pattern of residential segregation and income inequality.

Hate appreciates.

Houses with discriminatory covenants on the title are worth, on average, 15% more than a similar house without a covenant.

Research shows what communities of color have known for decades: Intentional structural barriers based on race worked in housing and elsewhere. They built the foundation for the disparities that exist today in Black household income, local school funding, access to health care, police and safety policies, green spaces and neighborhood parks, public transportation, convenient and affordable grocery stores and other retail opportunities, and nearby jobs that pay living wages.

Minnesota’s history of discriminatory covenants is well documented. The Just Deeds Coalition is dedicated to improving housing opportunities for all, today and tomorrow.